In the last decade and a half, there has arisen a class of problem that are becoming very critical in the computing domain. These problems deal with computing in a highly distributed environments. A key characteristic of this domain is the need to grow elastically with increasing workloads while tolerating failures without missing a beat. In short I would like to refer to this as ‘Web Scale Computing’ where the number of servers exceeds several 100’s and the data size is of the order of few hundred terabytes to several Exabytes.

There are several features that are unique to large scale distributed systems

- The servers used are not specialized machines but regular commodity, off-the-shelf servers

- Failures are not the exception but the norm. The design must be resilient to failures

- There is no global clock. Each individual server has its own internal clock with its own skew and drift rates. Algorithms exist that can create a notion of a global clock

- Operations happen at these machines concurrently. The order of the operations, things like causality and concurrency, can be evaluated through special algorithms like Lamport or Vector clocks

- The distributed system must be able to handle failures where servers crash, disk fails or there is a network problem. For this reason data is replicated across servers, so that if one server fails the data can still be obtained from copies residing on other servers.

- Since data is replicated there are associated issues of consistency. Algorithms exist that ensure that the replicated data is either ‘strongly’ consistent or ‘eventually’ consistent. Trade-offs are often considered when choosing one of the consistency mechanisms

- Leaders are elected democratically. Then there are dictators who get elected through ‘bully’ing.

In some ways distributed systems behave like a murmuration of starlings (or a school of fish), where a leader is elected on the fly (pun unintended) and the starlings or fishes change direction based on a few (typically 6) closest neighbors.

This series of posts, Thinking Web Scale (TWS) , will be about Web Scale problems and the algorithms designed to address this. I would like to keep these posts more essay-like and less pedantic.

In the early days, computing used to be done in a single monolithic machines with its own CPU, RAM and a disk., This situation was fine for a long time, as technology promptly kept its date with Moore’s Law which stated that the “ computing power and memory capacity’ will double every 18 months. However this situation changed drastically as the data generated from machines grew exponentially – whether it was the call detail records, records from retail stores, click streams, tweets, and status updates of social networks of today

These massive amounts of data cannot be handled by a single machine. We need to ‘divide’ and ‘conquer this data for processing. Hence there is a need for a hundreds of servers each handling a slice of the data.

The first post is about the fairly recent computing paradigm “Map-Reduce”. Map- Reduce is a product of Google Research and was developed to solve their need to calculate create an Inverted Index of Web pages, to compute the Page Rank etc. The algorithm was initially described in a white paper published by Google on the Map-Reduce algorithm. The Page Rank algorithm now powers Google’s search which now almost indispensable in our daily lives.

The Map-Reduce assumes that these servers are not perfect, failure-proof machines. Rather Map-Reduce folds into its design the assumption that the servers are regular, commodity servers performing a part of the task. The hundreds of terabytes of data is split into 16MB to 64MB chunks and distributed into a file system known as ‘Distributed File System (DFS)’. There are several implementations of the Distributed File System. Each chunk is replicated across servers. One of the servers is designated as the “Master’. This “Master’ allocates tasks to ‘worker’ nodes. A Master Node also keeps track of the location of the chunks and their replicas.

When the Map or Reduce has to process data, the process is started on the server in which the chunk of data resides.

The data is not transferred to the application from another server. The Compute is brought to the data and not the other way around. In other words the process is started on the server where the data, intermediate results reside

The reason for this is that it is more expensive to transmit data. Besides the latencies associated with data transfer can become significant with increasing distances

Map-Reduce had its genesis from a Lisp Construct of the same name

Where one could apply a common operation over a list of elements and then reduce the resulting list of elements with a reduce operation

The Map-Reduce was originally created by Google solve Page Rank problem Now Map-Reduce is used across a wide variety of problems.

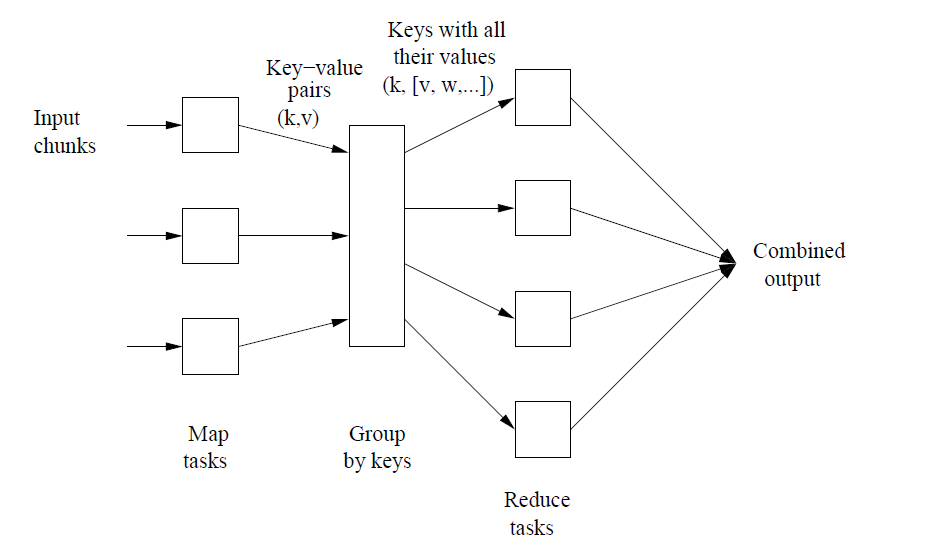

The main components of Map-Reduce are the following

- Mapper: Convert all d ∈ D to (key (d), value (d))

- Shuffle: Moves all (k, v) and (k’, v’) with k = k’ to same machine.

- Reducer: Transforms {(k, v1), (k, v2) . . .} to an output D’ k = f(v1, v2, . . .). …

- Combiner: If one machine has multiple (k, v1), (k, v2) with same k then it can perform part of Reduce before Shuffle

A schematic of the Map-Reduce is included below\

Map Reduce is usually a perfect fit for problems that have an inherent property of parallelism. To these class of problems the map-reduce paradigm can be applied in simultaneously to a large sets of data. The “Hello World” equivalent of Map-Reduce is the Word count problem. Here we simultaneously count the occurrences of words in millions of documents

The map operation scans the documents in parallel and outputs a key-value pair. The key is the word and the value is the number of occurrences of the word. E.g. In this case ‘map’ will scan each word and emit the word and the value 1 for the key-value pair

So, if the document contained

“All men are equal. Some men are more equal than others”

Map would output

(all,1), (men,1), (are,1), (equal,1), (some,1), (men,1), (are,1), (equal,1), (than,1), (others,1)

The Reduce phase will take the above output and give sum all key value pairs with the same key

(all,1), (men,2), (are,2),(equal,2), (than,1), (others,1)

So we get to count all the words in the document

In the Map-Reduce the Master node assigns tasks to Worker nodes which process the data on the individual chunks

Map-Reduce also makes short work of dealing with large matrices and can crunch matrix operations like matrix addition, subtraction, multiplication etc.

Matrix-Vector multiplication

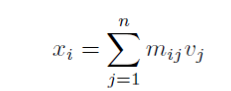

As an example if we consider a Matrix-Vector multiplication (taken from the book Mining Massive Data Sets by Jure Leskovec, Anand Rajaraman et al

For a n x n matrix if we have M with the value mij in the ith row and jth column. If we need to multiply this with a vector vj, then the matrix-vector product of M x vj is given by xi

Here the product of mij x vj can be performed by the map function and the summation can be performed by a reduce operation. The obvious question is, what if the vector vj or the matrix mij did not fit into memory. In such a situation the vector and matrix are divided into equal sized slices and performed acorss machines. The application would have to work on the data to consolidate the partial results.

Fortunately, several problems in Machine Learning, Computer Vision, Regression and Analytics which require large matrix operations. Map-Reduce can be used very effectively in matrix manipulation operations. Computation of Page Rank itself involves such matrix operations which was one of the triggers for the Map-Reduce paradigm.

Handling failures: As mentioned earlier the Map-Reduce implementation must be resilient to failures where failures are the norm and not the exception. To handle this the ‘master’ node periodically checks the health of the ‘worker’ nodes by pinging them. If the ping response does not arrive, the master marks the worker as ‘failed’ and restarts the task allocated to worker to generate the output on a server that is accessible.

Stragglers: Executing a job in parallel brings forth the famous saying ‘A chain is as strong as the weakest link’. So if there is one node which is straggler and is delayed in computation due to disk errors, the Master Node starts a backup worker and monitors the progress. When either the straggler or the backup complete, the master kills the other process.

Mining Social Networks, Sentiment Analysis of Twitterverse also utilize Map-Reduce.

However, Map-Reduce is not a panacea for all of the industry’s computing problems (see To Hadoop, or not to Hadoop)

But the Map-Reduce is a very critical paradigm in the distributed computing domain as it is able to handle mountains of data, can handle multiple simultaneous failures, and is blazingly fast.

Also see

1. A crime map of India in R: Crimes against women

2. What’s up Watson? Using IBM Watson’s QAAPI with Bluemix, NodeExpress – Part 1

3. Bend it like Bluemix, MongoDB with autoscaling – Part 2

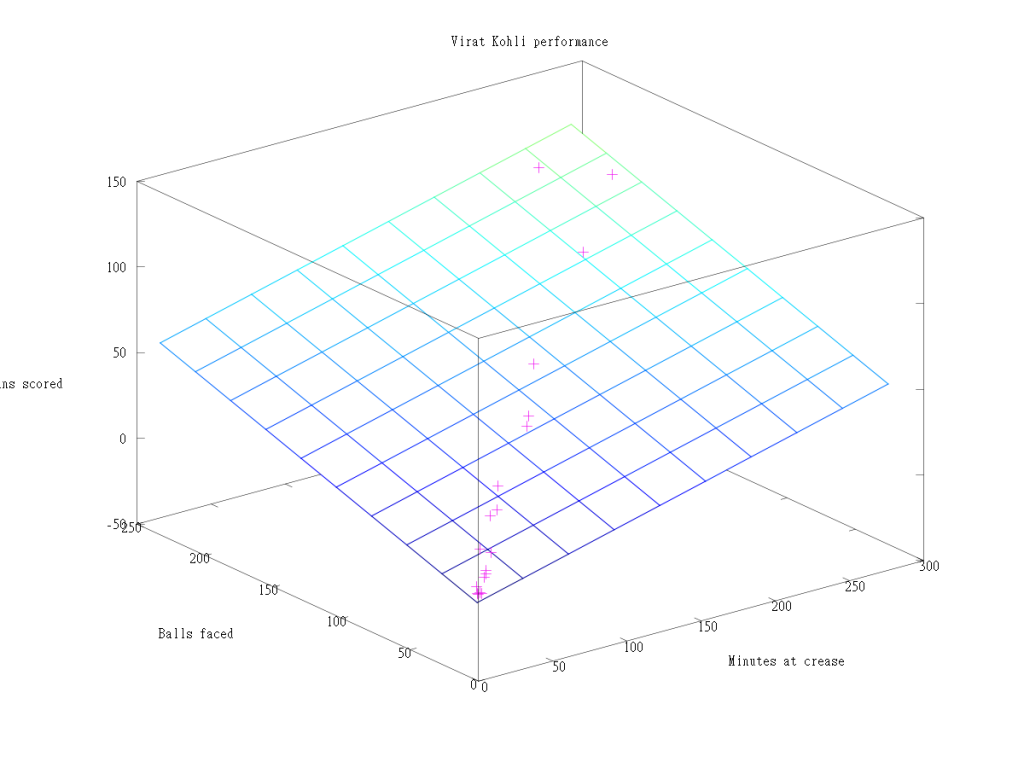

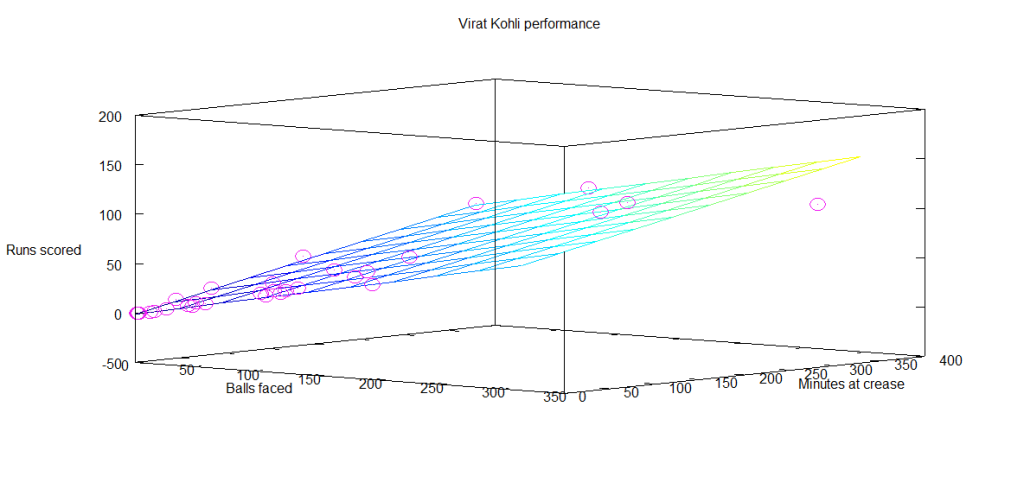

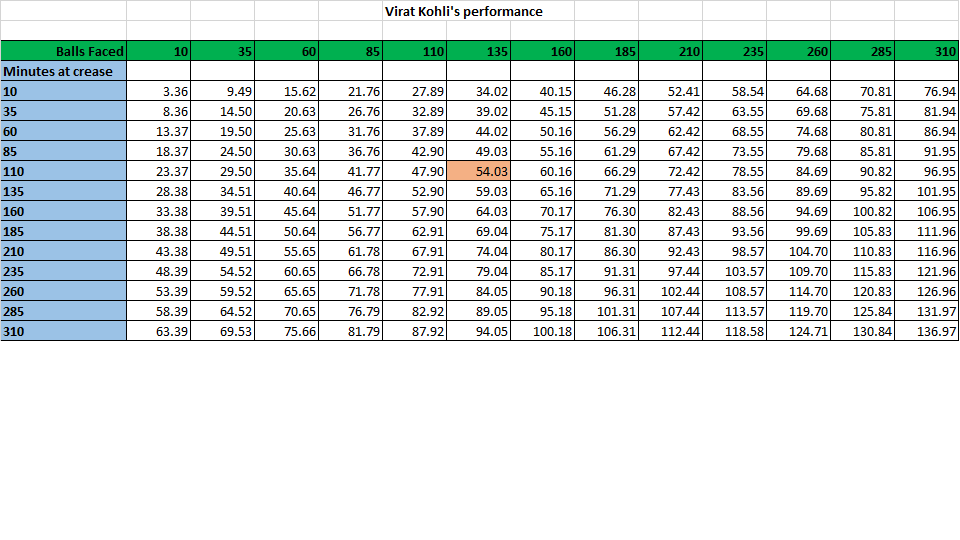

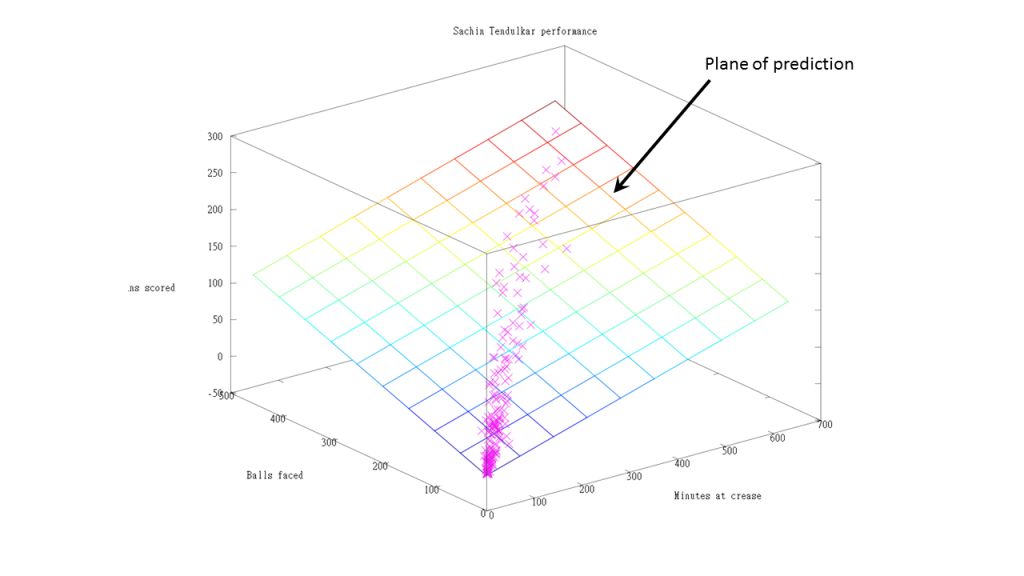

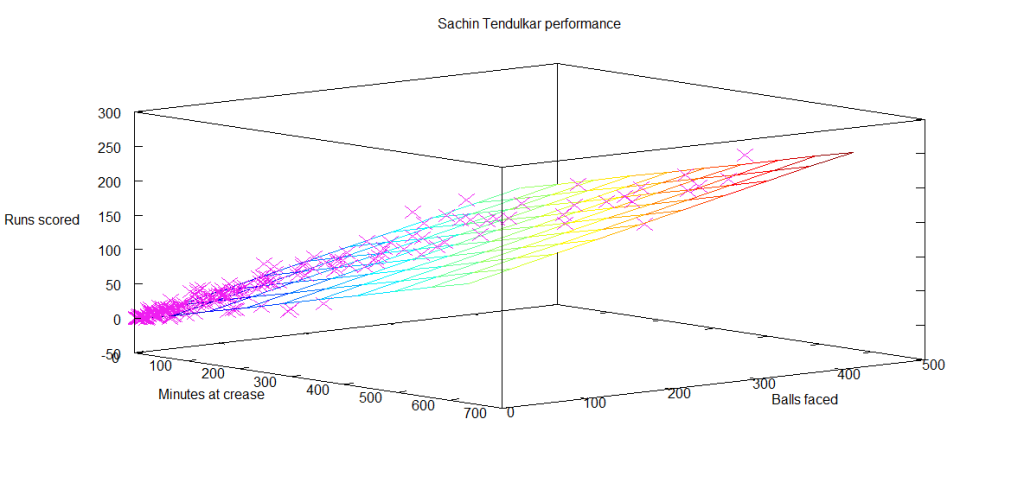

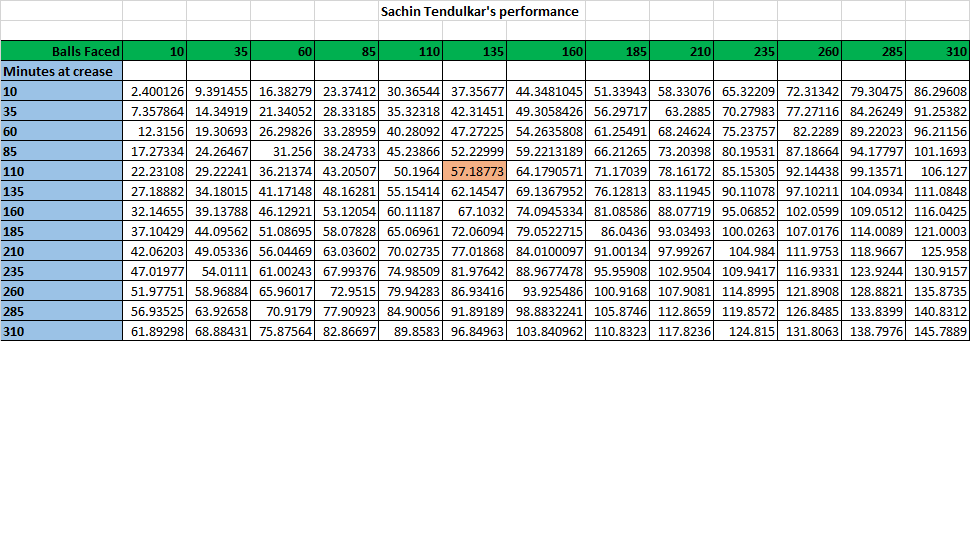

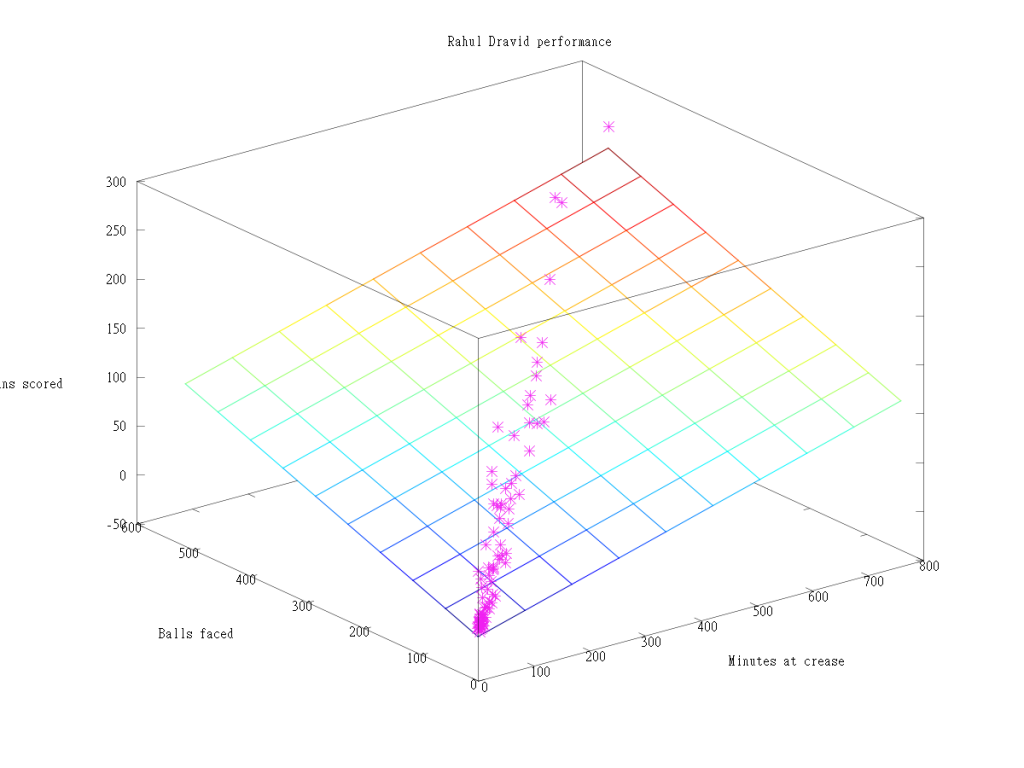

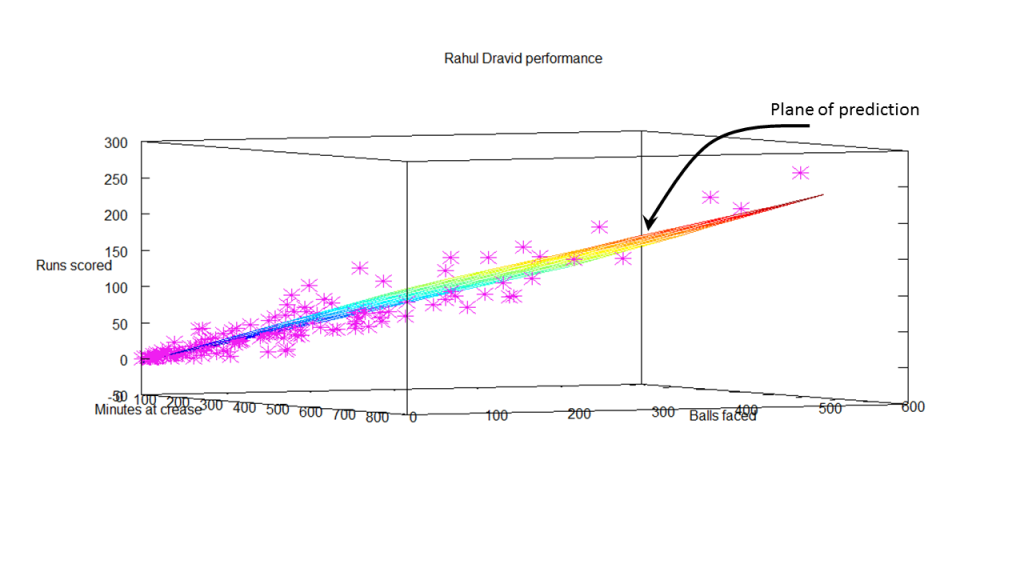

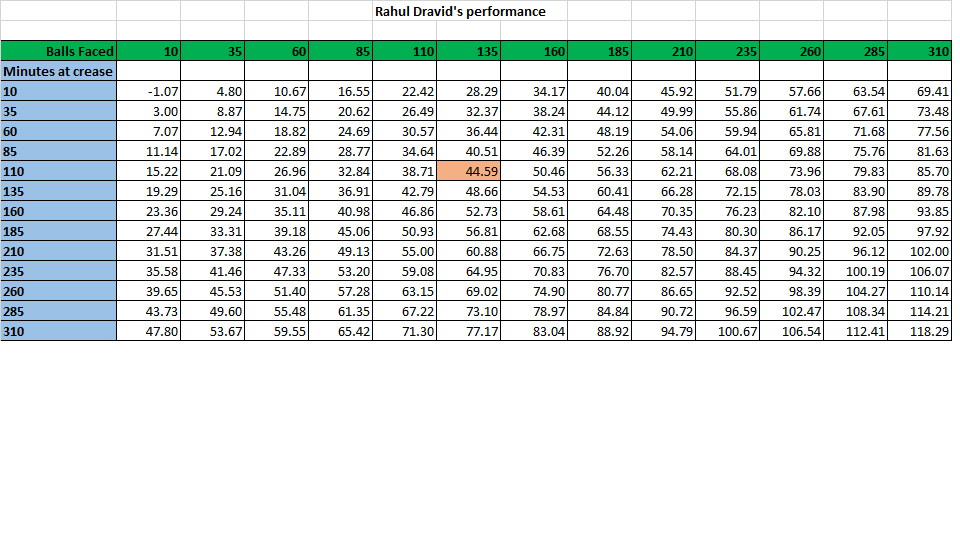

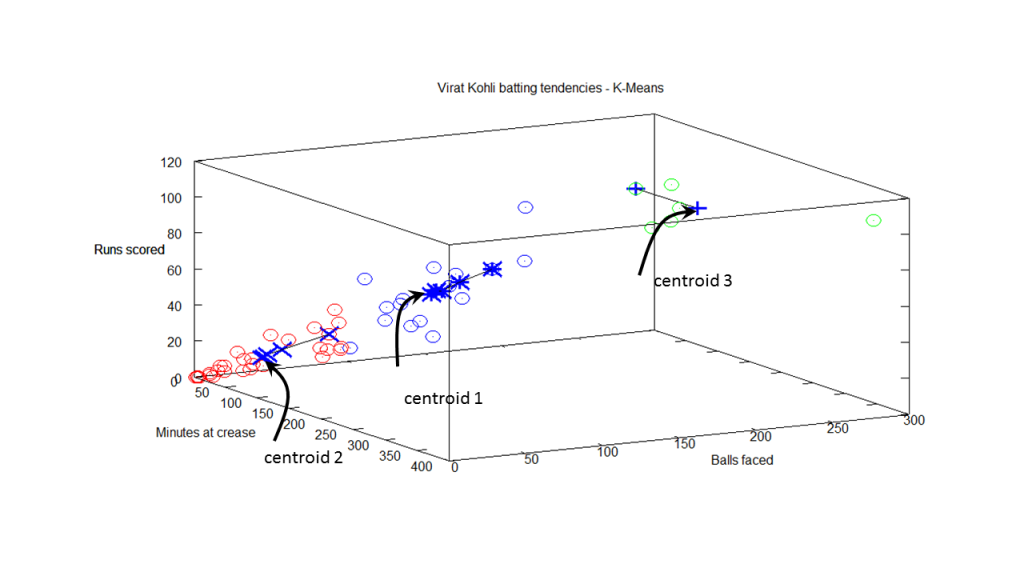

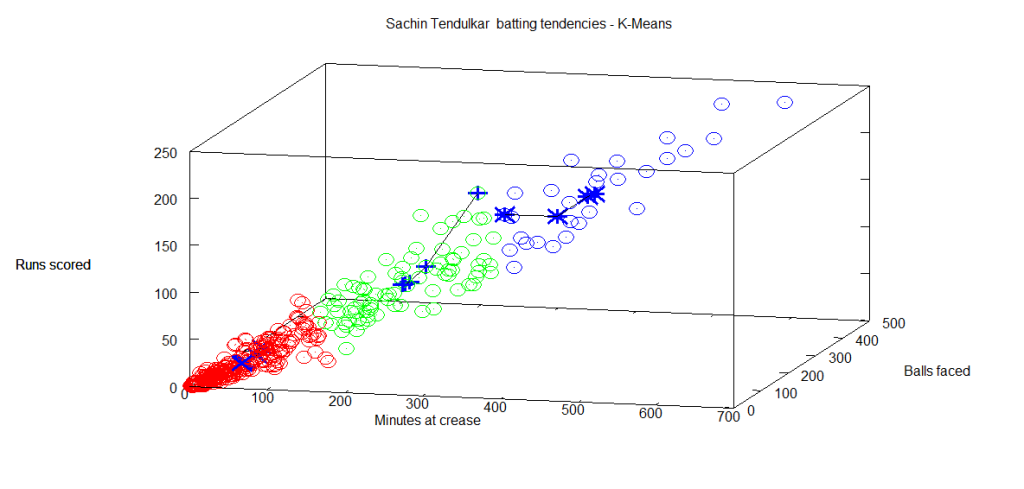

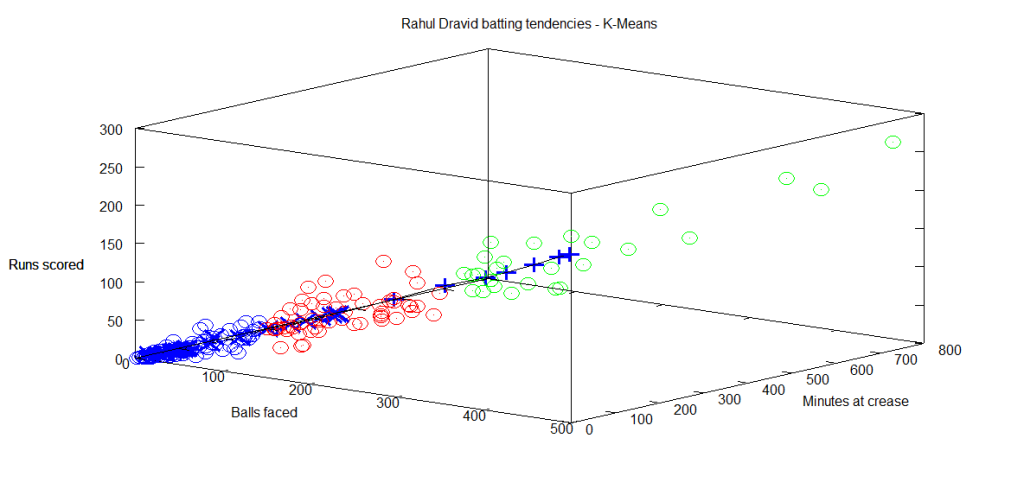

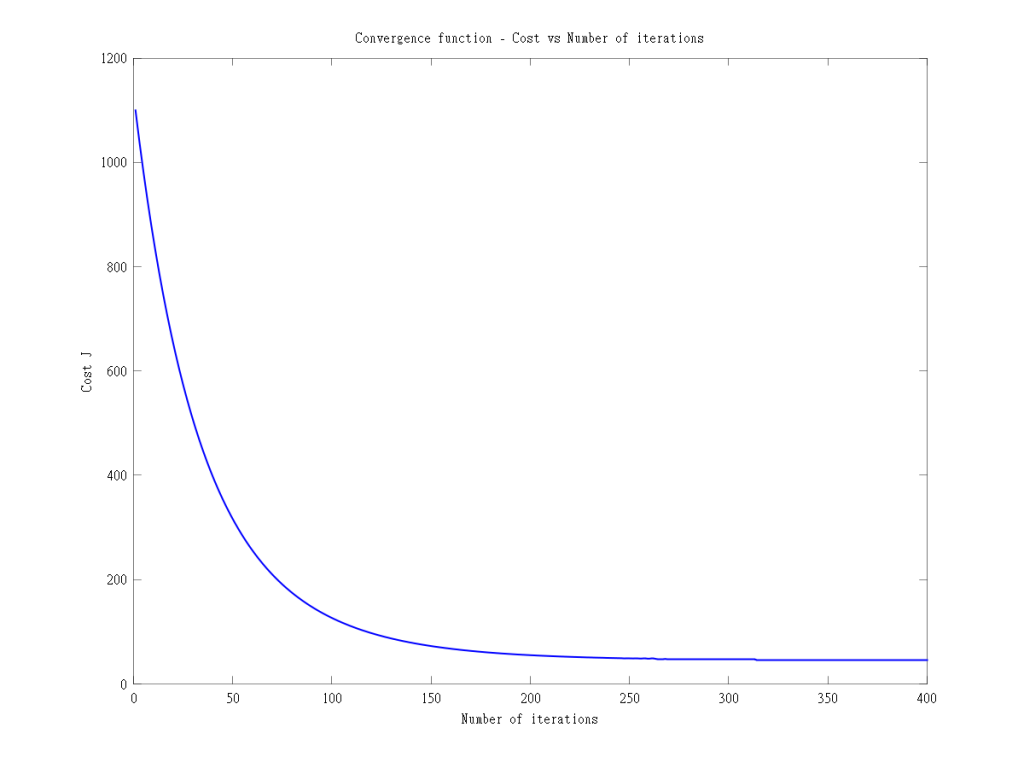

4. Informed choices through Machine Learning : Analyzing Kohli, Tendulkar and Dravid

To see all posts click ‘Index of Posts”