In this post, I revisit the visualisation of IPL batsman and bowler similarities using Google’s Embedding Projector. I had previously done this using multivariate regression in my earlier post ‘Using embeddings, collaborative filtering with Deep Learning to analyse T20 players.’ However, I was not too satisfied with the result since I was not getting the required accuracy.

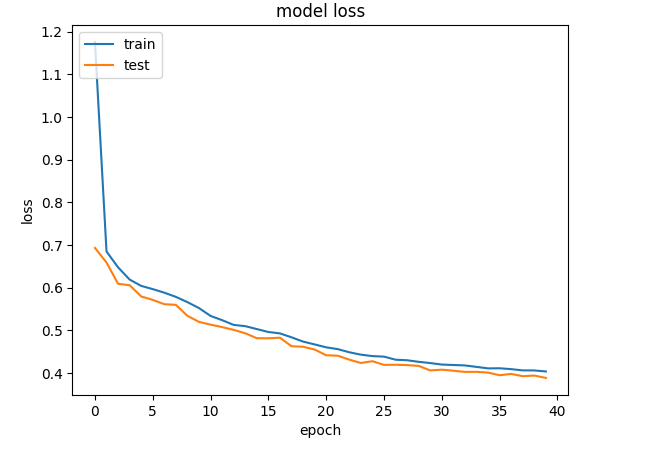

This post uses the win-loss status of IPL matches from 2014 onwards upto 2023 in Logistic Regression with Deep Learning. A 16-dimensional embedding layer is added for the batsman and the bowler for ball-by-ball data. Since I have used a reduced size data set (from 2014) I get a slightly reduced accuracy, but still I think this is a well-formulated problem.

A Deep Learning network performs gradient descent based using Adam optimisation to arrive at an accuracy of 0.8047. The weights of the learnt Deep Learning network in ‘layer 0’ is used for displaying the batsman and bowler similarities.

Similarity measures – Cosine similarity

A cosine similarity is a value that is bound by a constrained range of 0 and 1. The closer the value is to 0 means that the two vectors are orthogonal or perpendicular to each other. When the value is closer to one, it means the angle is smaller and the batsman and bowler are similar.

a) Data set

For the data set only IPL T20 matches from Jan 2014 upto the present (May 2023) was taken. A Deep Learning model using Logistic Regression with batsman and bowler embedding is used to minimise the error. An accuracy of 0.8047 is obtained. In my earlier post ‘GooglyPlusPlus: Win Probability using Deep Learning and player embeddings‘ I had used data from all T20 leagues (~1.2 million rows) and got an accuracy of 0.8647

b) Import the data

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from zipfile import ZipFile

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow import keras

from tensorflow.keras import layers

from tensorflow.keras import regularizers

from pathlib import Path

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from zipfile import ZipFile

import tensorflow as tf

from tensorflow import keras

from tensorflow.keras import layers

from tensorflow.keras import regularizers

df1=pd.read_csv('ipl2014_23.csv')

print("Shape of dataframe=",df1.shape)

train_dataset = df1.sample(frac=0.8,random_state=0)

test_dataset = df1.drop(train_dataset.index)

train_dataset1 = train_dataset[['batsmanIdx','bowlerIdx','ballNum','ballsRemaining','runs','runRate','numWickets','runsMomentum','perfIndex']]

test_dataset1 = test_dataset[['batsmanIdx','bowlerIdx','ballNum','ballsRemaining','runs','runRate','numWickets','runsMomentum','perfIndex']]

train_dataset1

train_labels = train_dataset.pop('isWinner')

test_labels = test_dataset.pop('isWinner')

train_dataset1

a=train_dataset1.describe()

stats=a.transpose

Shape of dataframe= (138896, 10)

batsmanIdx bowlerIdx ballNum ballsRemaining runs runRate numWickets runsMomentum perfIndex

count 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000 111117.000000

mean 218.672939 169.204145 120.372067 60.749822 86.881701 1.636353 2.423167 0.296061 10.578927

std 118.405729 96.934754 69.991408 35.298794 51.643164 2.672564 2.085956 0.620872 4.436981

min 1.000000 1.000000 1.000000 1.000000 -5.000000 -5.000000 0.000000 0.057143 0.000000

25% 111.000000 89.000000 60.000000 30.000000 45.000000 1.160000 1.000000 0.106383 7.733333

50% 220.000000 170.000000 119.000000 60.000000 85.000000 1.375000 2.000000 0.142857 10.329545

75% 325.000000 249.000000 180.000000 91.000000 126.000000 1.640000 4.000000 0.240000 13.108696

max 411.000000 332.000000 262.000000 135.000000 258.000000 251.000000 10.000000 11.000000 66.000000c) Create a Deep Learning ML model using batsman & bowler embeddings

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from keras.layers import Input, Embedding, Flatten, Dense

from keras.models import Model

from keras.layers import Input, Embedding, Flatten, Dense, Reshape, Concatenate, Dropout

from keras.models import Model

tf.random.set_seed(432)

# create input layers for each of the predictors

batsmanIdx_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='batsmanIdx')

bowlerIdx_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='bowlerIdx')

ballNum_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='ballNum')

ballsRemaining_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='ballsRemaining')

runs_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='runs')

runRate_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='runRate')

numWickets_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='numWickets')

runsMomentum_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='runsMomentum')

perfIndex_input = Input(shape=(1,), name='perfIndex')

# Set the embedding size

no_of_unique_batman=len(df1["batsmanIdx"].unique())

print(no_of_unique_batman)

no_of_unique_bowler=len(df1["bowlerIdx"].unique())

print(no_of_unique_bowler)

embedding_size_bat = no_of_unique_batman ** (1/4)

embedding_size_bwl = no_of_unique_bowler ** (1/4)

# create embedding layer for the categorical predictor

batsmanIdx_embedding = Embedding(input_dim=no_of_unique_batman+1, output_dim=16,input_length=1)(batsmanIdx_input)

batsmanIdx_flatten = Flatten()(batsmanIdx_embedding)

bowlerIdx_embedding = Embedding(input_dim=no_of_unique_bowler+1, output_dim=16,input_length=1)(bowlerIdx_input)

bowlerIdx_flatten = Flatten()(bowlerIdx_embedding)

# concatenate all the predictors

x = keras.layers.concatenate([batsmanIdx_flatten,bowlerIdx_flatten, ballNum_input, ballsRemaining_input, runs_input, runRate_input, numWickets_input, runsMomentum_input, perfIndex_input])

# add hidden layers

#x = Dense(64, activation='relu')(x)

#x = Dropout(0.1)(x)

x = Dense(32, activation='relu')(x)

x = Dropout(0.1)(x)

x = Dense(16, activation='relu')(x)

x = Dropout(0.1)(x)

x = Dense(8, activation='relu')(x)

x = Dropout(0.1)(x)

# add output layer

output = Dense(1, activation='sigmoid', name='output')(x)

print(output.shape)

# create model

model = Model(inputs=[batsmanIdx_input,bowlerIdx_input, ballNum_input, ballsRemaining_input, runs_input, runRate_input, numWickets_input, runsMomentum_input, perfIndex_input], outputs=output)

model.summary()

# compile model

optimizer=keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=.01, beta_1=0.9, beta_2=0.999, epsilon=1e-07, amsgrad=True)

model.compile(optimizer=optimizer, loss='binary_crossentropy', metrics=['accuracy'])

# train the model

history=model.fit([train_dataset1['batsmanIdx'],train_dataset1['bowlerIdx'],train_dataset1['ballNum'],train_dataset1['ballsRemaining'],train_dataset1['runs'],

train_dataset1['runRate'],train_dataset1['numWickets'],train_dataset1['runsMomentum'],train_dataset1['perfIndex']], train_labels, epochs=40, batch_size=1024,

validation_data = ([test_dataset1['batsmanIdx'],test_dataset1['bowlerIdx'],test_dataset1['ballNum'],test_dataset1['ballsRemaining'],test_dataset1['runs'],

test_dataset1['runRate'],test_dataset1['numWickets'],test_dataset1['runsMomentum'],test_dataset1['perfIndex']],test_labels), verbose=1)

plt.plot(history.history["loss"])

plt.plot(history.history["val_loss"])

plt.title("model loss")

plt.ylabel("loss")

plt.xlabel("epoch")

plt.legend(["train", "test"], loc="upper left")

plt.show()

d) Project embeddings with Google’s Embedding projector

try:

# %tensorflow_version only exists in Colab.

%tensorflow_version 2.x

except Exception:

pass

%load_ext tensorboard

import os

import tensorflow as tf

import tensorflow_datasets as tfds

from tensorboard.plugins import projector

%pwd

# Set up a logs directory, so Tensorboard knows where to look for files.

log_dir='/logs/batsmen/'

if not os.path.exists(log_dir):

os.makedirs(log_dir)

df3=pd.read_csv('batsmen.csv')

batsmen = df3["batsman"].unique().tolist()

batsmen

# Create dictionary of batsman to index

batsmen2index = {x: i for i, x in enumerate(batsmen)}

batsmen2index

# Create dictionary of index to batsman

index2batsmen = {i: x for i, x in enumerate(batsmen)}

index2batsmen

# Save Labels separately on a line-by-line manner.

with open(os.path.join(log_dir, 'metadata.tsv'), "w") as f:

for batsmanIdx in range(1, 411):

# Get the name of batsman associated at the current index

batsman = index2batsmen.get([batsmanIdx][0])

f.write("{}\n".format(batsman))

# Save the weights we want to analyze as a variable. Note that the first

# value represents any unknown word, which is not in the metadata, here

# we will remove this value.

weights = tf.Variable(model.get_weights()[0][1:])

print(weights)

print(type(weights))

print(len(model.get_weights()[0]))

# Create a checkpoint from embedding, the filename and key are the

# name of the tensor.

checkpoint = tf.train.Checkpoint(embedding=weights)

checkpoint.save(os.path.join(log_dir, "embedding.ckpt"))

# Set up config.

config = projector.ProjectorConfig()

embedding = config.embeddings.add()

# The name of the tensor will be suffixed by `/.ATTRIBUTES/VARIABLE_VALUE`.

embedding.tensor_name = "embedding/.ATTRIBUTES/VARIABLE_VALUE"

embedding.metadata_path = 'metadata.tsv'

projector.visualize_embeddings(log_dir, config)

# Now run tensorboard against on log data we just saved.

%reload_ext tensorboard

%tensorboard --logdir /logs/batsmen/e) Here are similarity measures for some batsmen

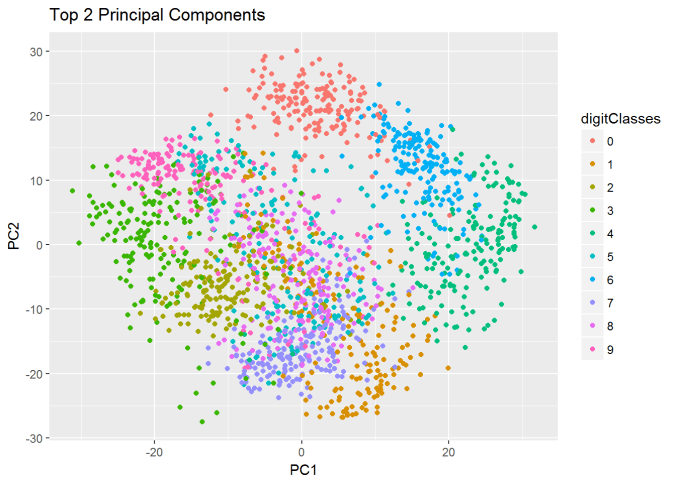

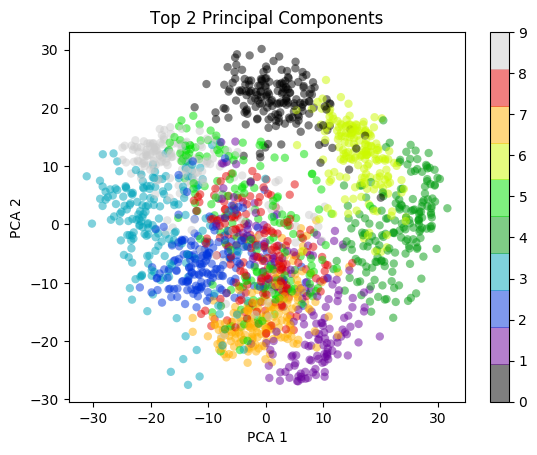

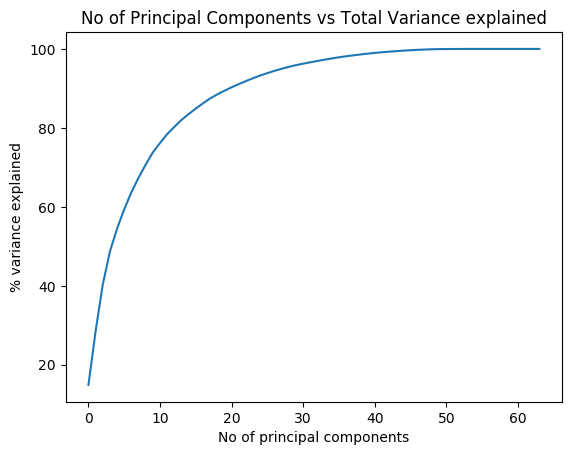

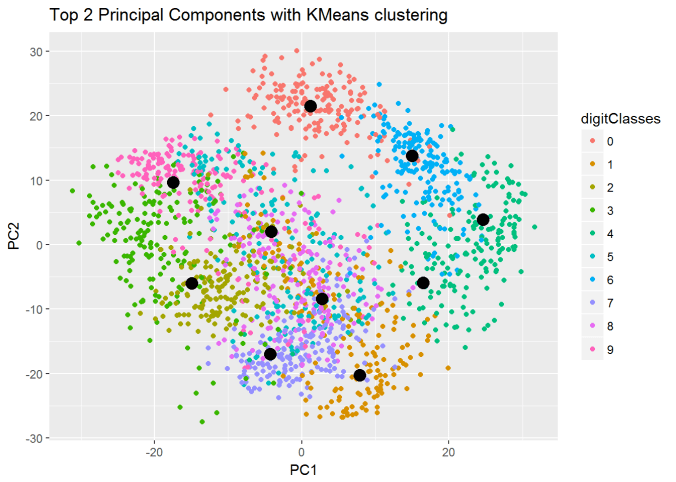

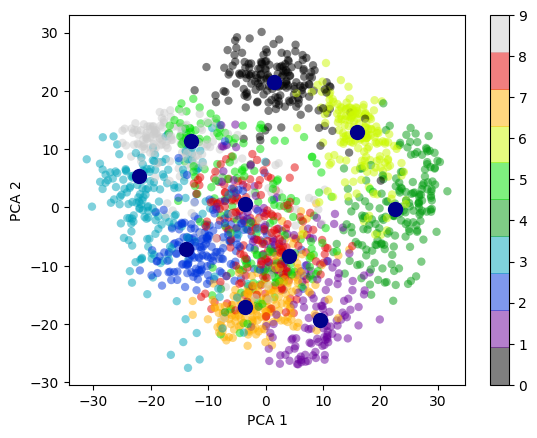

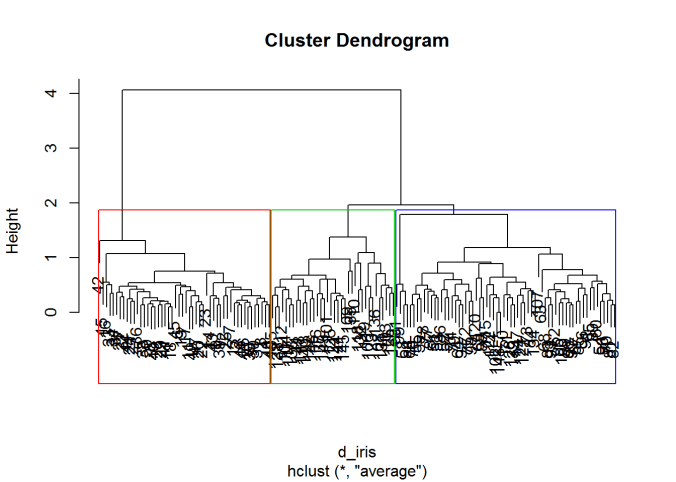

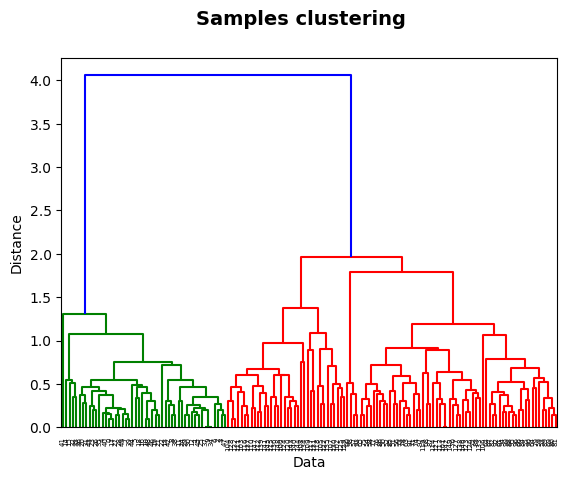

I) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) : In the charts and video animation below, the 16-dimensional embedding vector of batsmen and bowler is reduced to 3 principal components in a lower dimension for visualisation and analysis as shown below

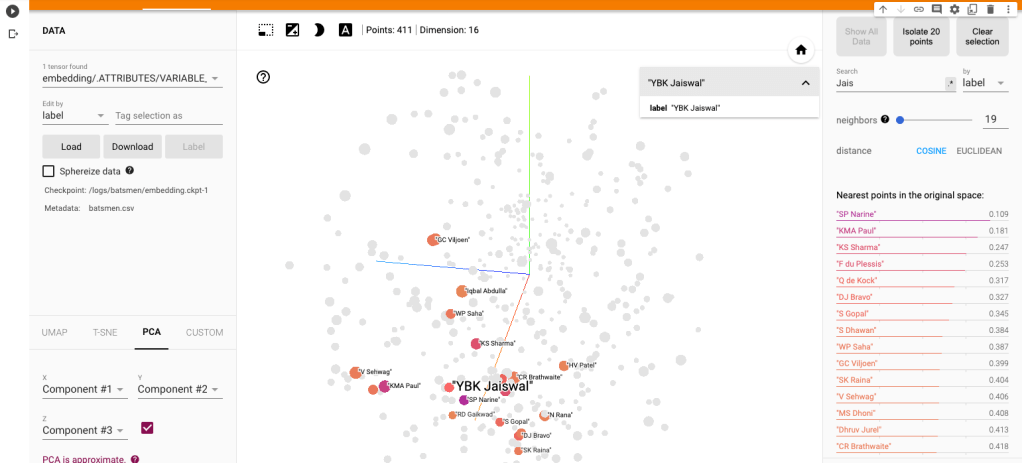

a) Yashasvi Jaiswal (similar players

i) PCA – Chart

Yashasvi Jaiswal style of attack is similar to Faf Du Plessis, Quentim De Kock, Bravo etc. In the below chart the ange between Jaiswal and SP Narine is 0.109, and Faf du Plessis is 0.253. These represent the angle in radians. The smaller the angle the more similar the performance style of the players and cos 0=1 or the players are similar.

ii) PCA animation video for Yashasvi Jaiswal

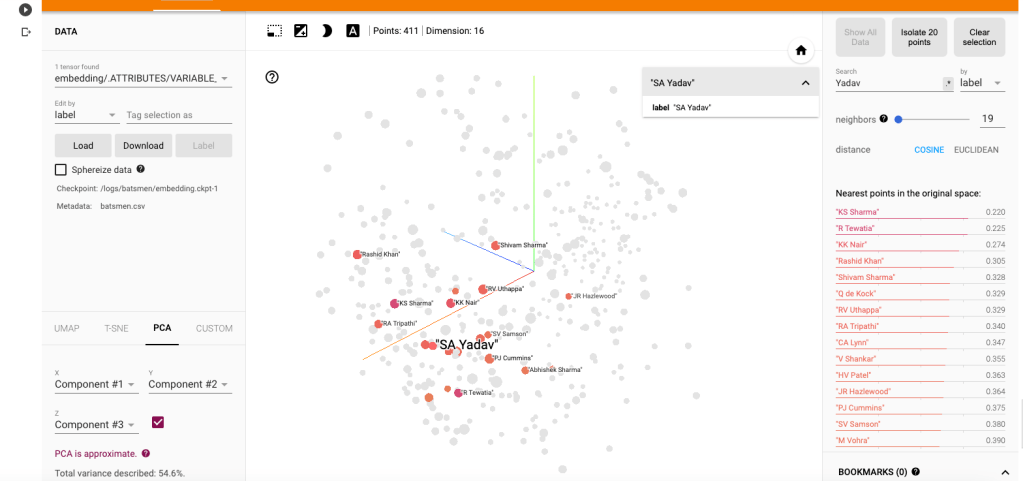

b) Suryakumar Yadav (SKY)

i) PCA -Chart

The closest neighbours for SKY is RV Uthappa, Rahul Tripathi, Q de Kock, Samson, Rashid Khan

ii) PCA – Animation video for Suryakumar Yadav

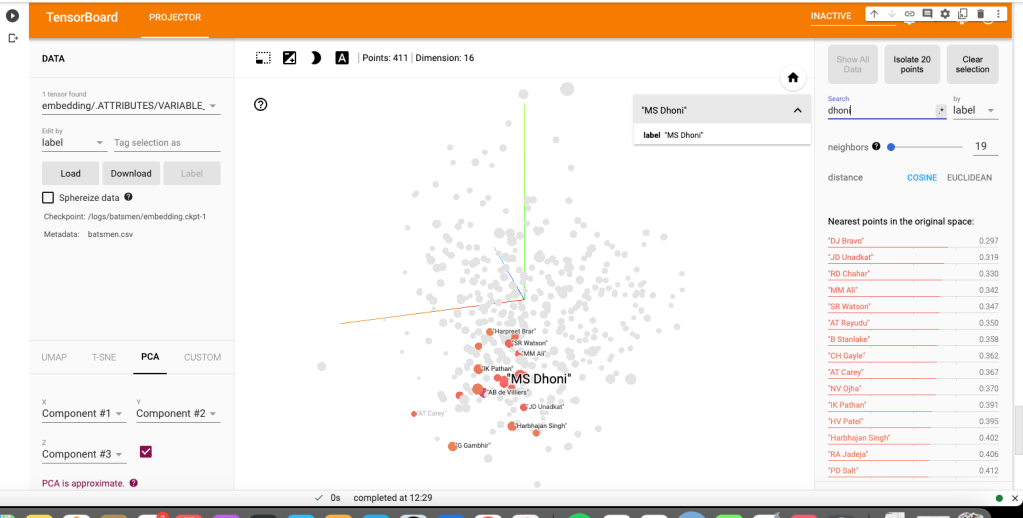

c) M S Dhoni

i) PCA – Chart

Dhoni rubs shoulders with Bravo, AB De Villiers, Shane Watson, Chris Gayle, Rayadu, Gautam Gambhir

ii) PCA – Animation video for M S Dhoni

f) PCA Analysis for bowlers

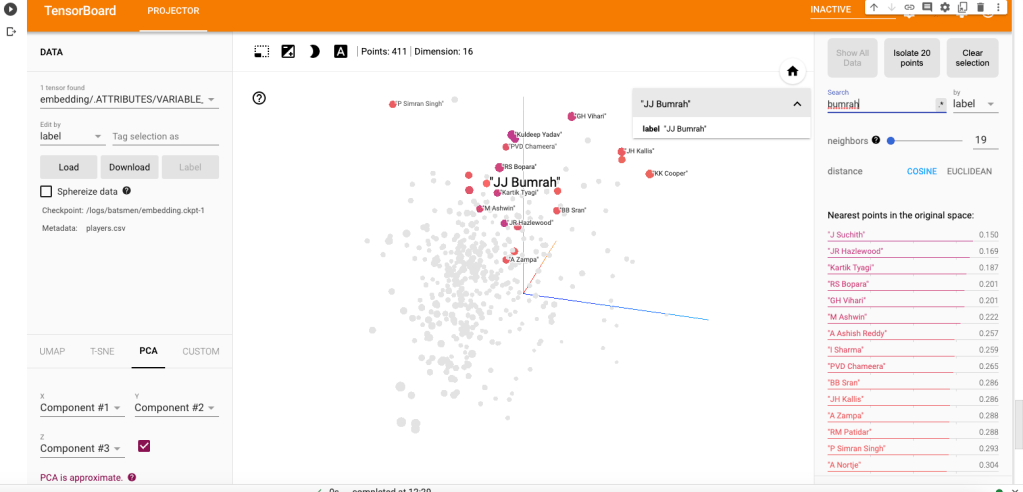

a) Jasprit Bumrah

i) PCA – Chart

Bumrah bowling performance is similar to Josh Hazzlewood, Chameera, Kuldeep Yadav, Nortje, Adam Zampa etc.

ii) PCA Animation video for Jasprit Bumrah

b) Yuzhvendra Chahal

i) PCA – Chart

Chahal’s performance has a strong similarity to Malinga, Zaheer Khan, Imran Tahir, R Sheperd, Adil Rashid

ii) PCA Animation video for YS Chahal

f) Other similarity measures ( t-SNE & UMAP)

There are 2 other similarity visualisations in Google’s Embedding Projector namely

i) t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) – t-SNE tries to find a faithful representation of the data distribution in higher dimensional space to a lower dimensional space. t-SNE differs from PCA by preserving only or local similarities whereas PCA is maintains preserving large pairwise distances.

a) t-SNE Animation video

ii) UMAP – Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection

UMAP learns the manifold structure of the high dimensional data and finds a low dimensional embedding that preserves the essential topological structure of that manifold.

ii) UMAP – Animation video

The Embedding projector thus helps in identifying players based on how they perform against bowlers, and probably picks up a lot of features like strike rate and performance in different stages of the game.

Hope you enjoyed the post!

Also see

- Exploring Quantum Gate operations with QCSimulator

- De-blurring revisited with Wiener filter using OpenCV

- Using Reinforcement Learning to solve Gridworld

- Deep Learning from first principles in Python, R and Octave – Part 4

- Big Data 6: The T20 Dance of Apache NiFi and yorkpy

- Latency, throughput implications for the Cloud

- Programming languages in layman’s language

- Practical Machine Learning with R and Python – Part 6

- Using Linear Programming (LP) for optimizing bowling change or batting lineup in T20 cricket

- A closer look at “Robot Horse on a Trot” in Android

To see all posts click Index of posts