Presenting ‘Googly’, a cool Shiny app that I developed over the last couple of days. This interactive Shiny app was on my mind for quite some time, and I finally got down to implementing it. The Googly Shiny app is based on my R package ‘yorkr’ which is now available in CRAN. The R package and hence this Shiny app is based on data from Cricsheet.

If you are passionate about cricket, and love analyzing cricket performances, then check out my 2 racy books on cricket! In my books, I perform detailed yet compact analysis of performances of both batsmen, bowlers besides evaluating team & match performances in Tests , ODIs, T20s & IPL. You can buy my books on cricket from Amazon at $12.99 for the paperback and $4.99/$6.99 respectively for the kindle versions. The books can be accessed at Cricket analytics with cricketr and Beaten by sheer pace-Cricket analytics with yorkr A must read for any cricket lover! Check it out!!

Googly is based on R package yorkr, and uses the data of all IPL matches from 2008 up to 2016, available on Cricsheet.

Googly can do detailed analyses of a) Individual IPL batsman b) Individual IPL bowler c) Any IPL match d) Head to head confrontation between 2 IPL teams e) All matches of an IPL team against all other teams.

With respect to the individual IPL batsman and bowler performance, I was in a bit of a ‘bind’ literally (pun unintended), as any IPL player could have played in more than 1 IPL team. Fortunately ‘rbind’ came to my rescue. I just get all the batsman’s/bowler’s performance in each IPL team, and then consolidate it into a single large dataframe to do the analyses of.

The Shiny app can be accessed at Googly

The code for Googly is available at Github. Feel free to clone/download/fork the code from Googly

Check out my 2 books on cricket, a) Cricket analytics with cricketr b) Beaten by sheer pace – Cricket analytics with yorkr, now available in both paperback & kindle versions on Amazon!!! Pick up your copies today!

Also see my post GooglyPlus: yorkr analyzes IPL players, teams, matches with plots and tables

Based on the 5 detailed analysis domains there are 5 tabs

IPL Batsman: This tab can be used to perform analysis of all IPL batsman. If a batsman has played in more than 1 team, then the overall performance is considered. There are 10 functions for the IPL Batsman. They are shown below

- Batsman Runs vs. Deliveries

- Batsman’s Fours & Sixes

- Dismissals of batsman

- Batsman’s Runs vs Strike Rate

- Batsman’s Moving Average

- Batsman’s Cumulative Average Run

- Batsman’s Cumulative Strike Rate

- Batsman’s Runs against Opposition

- Batsman’s Runs at Venue

- Predict Runs of batsman

IPL Bowler: This tab can be used to analyze individual IPL bowlers. The functions handle IPL bowlers who have played in more than 1 IPL team.

- Mean Economy Rate of bowler

- Mean runs conceded by bowler

- Bowler’s Moving Average

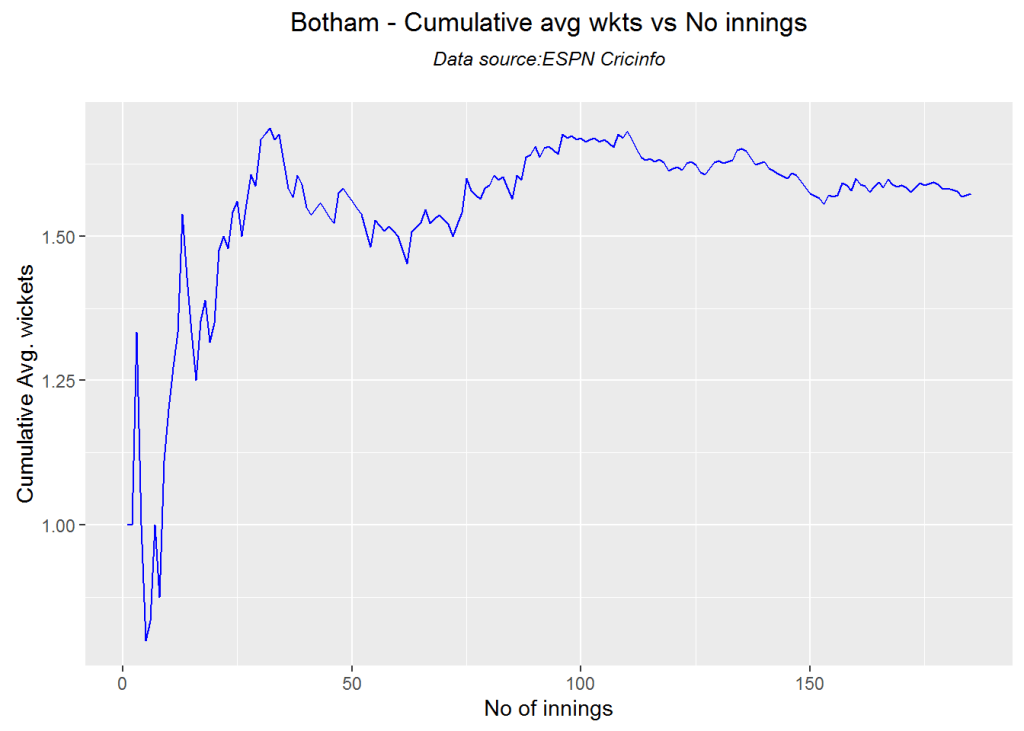

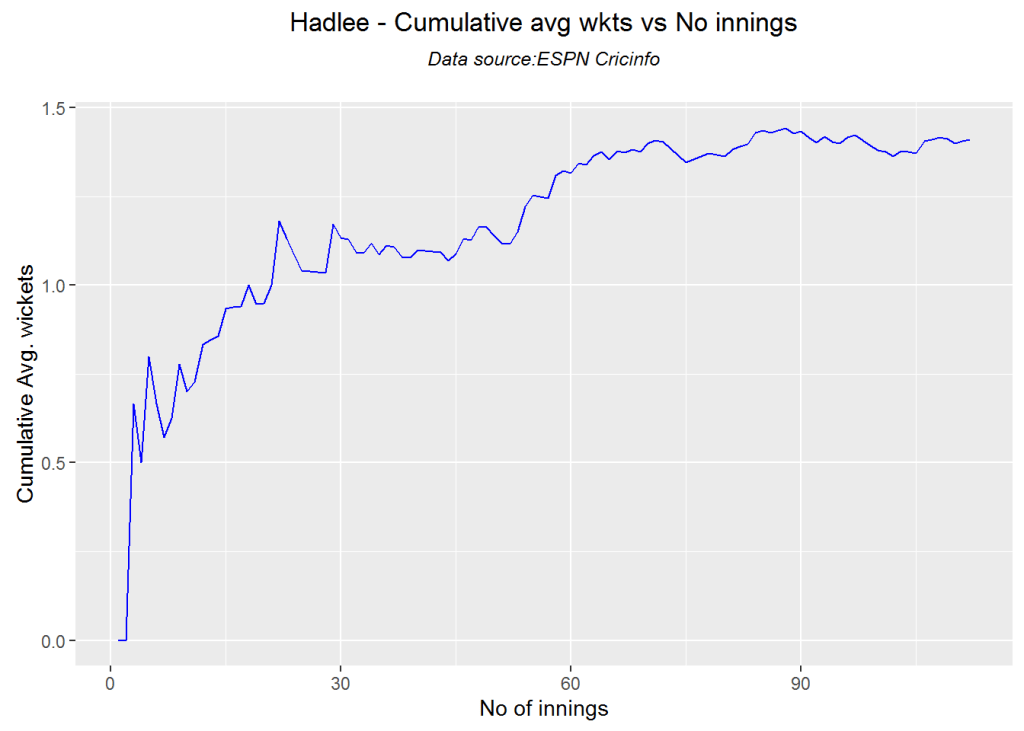

- Bowler’s Cumulative Avg. Wickets

- Bowler’s Cumulative Avg. Economy Rate

- Bowler’s Wicket Plot

- Bowler’s Wickets against opposition

- Bowler’s Wickets at Venues

- Bowler’s wickets prediction

IPL match: This tab can be used for analyzing individual IPL matches. The available functions are

- Batting Partnerships

- Batsmen vs Bowlers

- Bowling Wicket Kind

- Bowling Wicket Runs

- Bowling Wicket Match

- Bowler vs Batsmen

- Match Worm Graph

Head to head : This tab can be used for analyzing head-to-head confrontations, between any 2 IPL teams for e.g. all matches between Chennai Super Kings vs. Deccan Chargers or Kolkata Knight Riders vs. Delhi Daredevils. The available functions are

- Team Batsmen Batting Partnerships All Matches

- Team Batsmen vs Bowlers all Matches

- Team Wickets Opposition All Matches

- Team Bowler vs Batsmen All Matches

- Team Bowlers Wicket Kind All Matches

- Team Bowler Wicket Runs All Matches

- Win Loss All Matches

Overall performance : this tab can be used analyze the overall performance of any IPL team. For this analysis all matches played by this team is considered. The available functions are

- Team Batsmen Partnerships Overall

- Team Batsmen vs Bowlers Overall

- Team Bowler vs Batsmen Overall

- Team Bowler Wicket Kind Overall

Below I include a random set of charts that are generated in each of the 5 tabs

A. IPL Batsman

a. A Symonds : Runs vs Deliveries

b. AB Devilliers – Cumulative Strike Rate

c. Gautam Gambhir – Runs at venues

B. IPL Bowler

a. Ashish Nehra – Cumulative Average Wickets

b. DJ Bravo – Moving Average of wickets

c. R Ashwin – Mean Economy rate vs Overs

C.IPL Match

a. Chennai Super Kings vs Deccan Chargers (2008 -05-06) – Batsmen Partnerships

Note: You can choose either team in the match from the drop down ‘Choose team’

b. Kolkata Knight Riders vs Delhi Daredevils (2013-04-02) – Bowling wicket runs

c. Mumbai Indians vs Kings XI Punjab (2010-03-30) – Match worm graph

D. Head to head confrontation

a. Rising Pune Supergiants vs Mumbai Indians in all matches – Team batsmen partnerships

Note: You can choose the partnership of either team in the drop down ‘Choose team’

b. Gujarat Lions – Royal Challengers Bangalore all matches – Bowlers performance against batsmen

E. Overall Performance

a. Royal Challengers Bangalore overall performance – Batsman Partnership (Rank=1)

This is Virat Kohli for RCB. Try out other ranks

b. Rajashthan Royals overall Performance – Bowler vs batsman (Rank =2)

This is Vinay Kumar.

The Shiny app Googly can be accessed at Googly. Feel free to clone/fork the code from Github at Googly

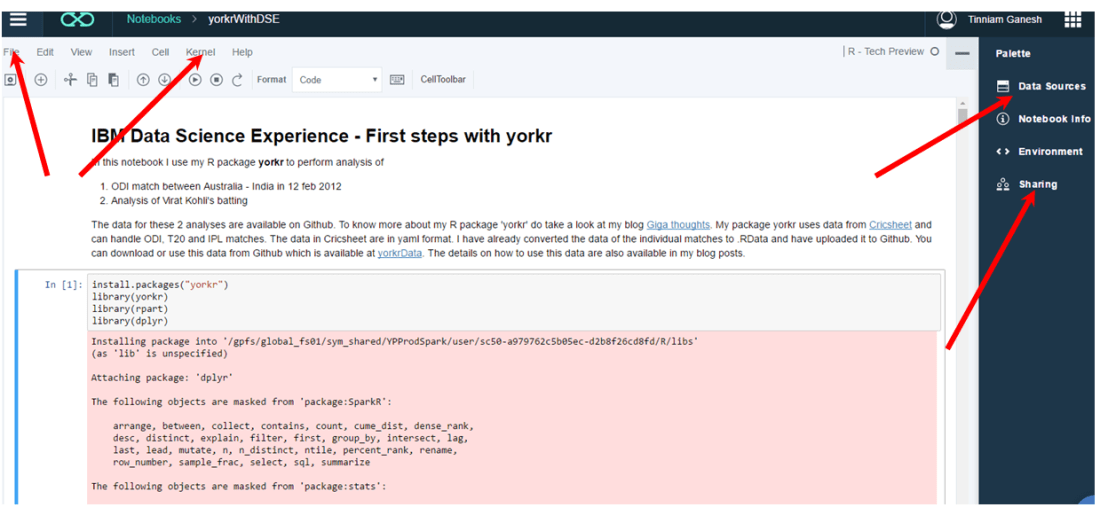

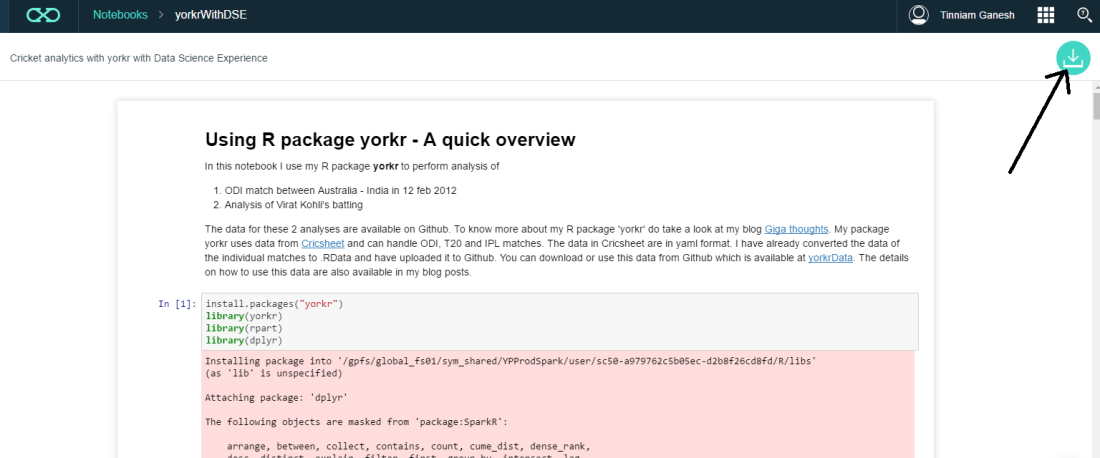

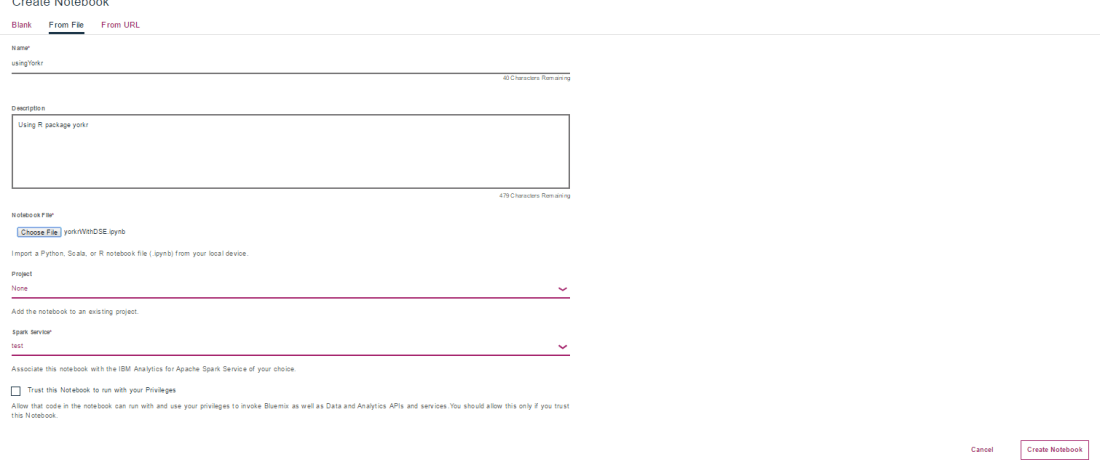

For details on my R package yorkr, please see my blog Giga thoughts. There are more than 15 posts detailing the functions and their usage.

Do bowl a Googly!!!

You may like my other Shiny apps

Also see my other posts

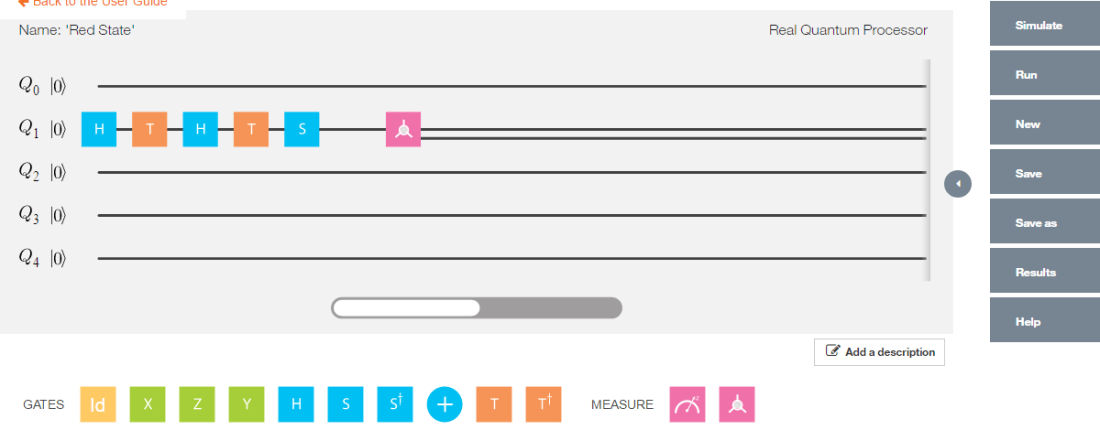

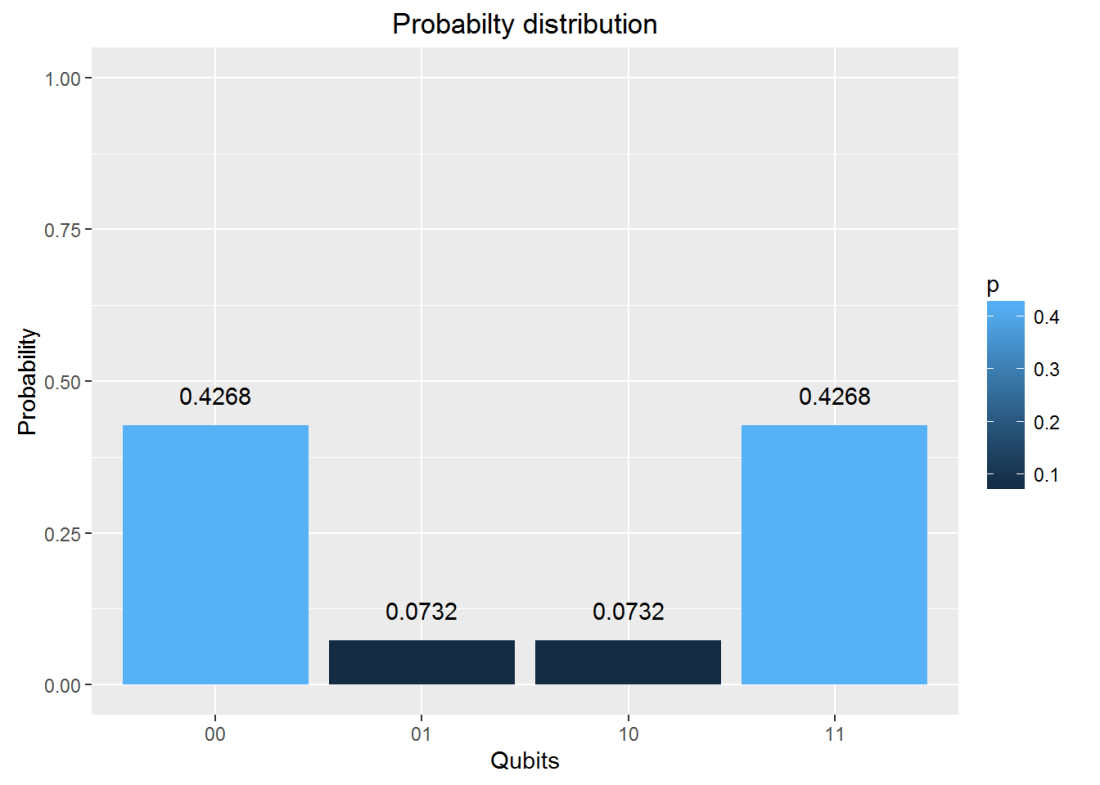

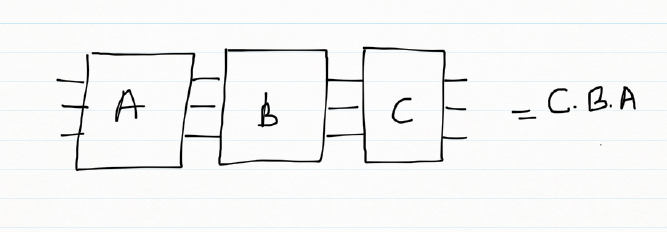

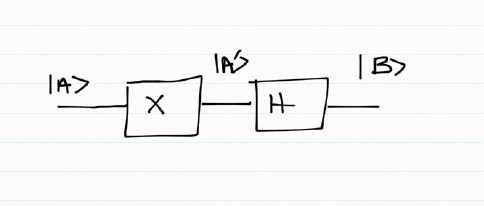

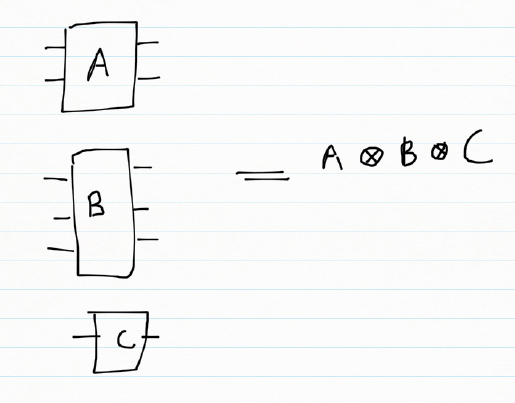

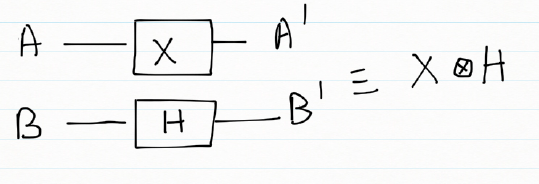

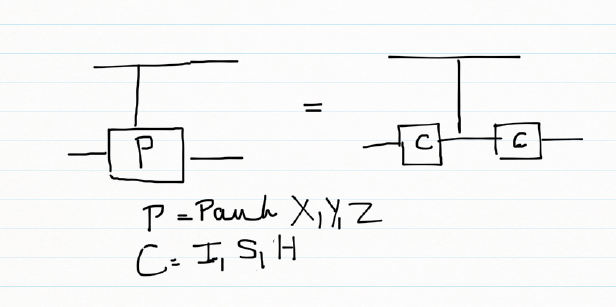

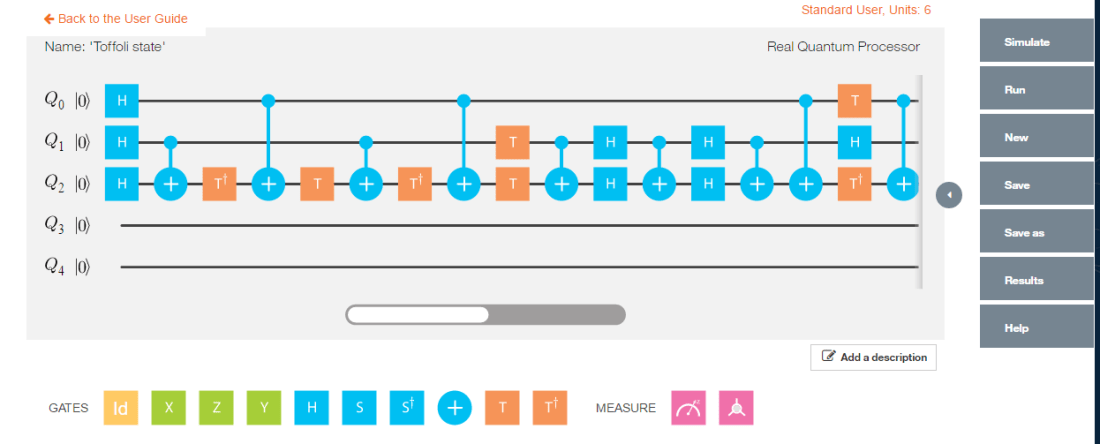

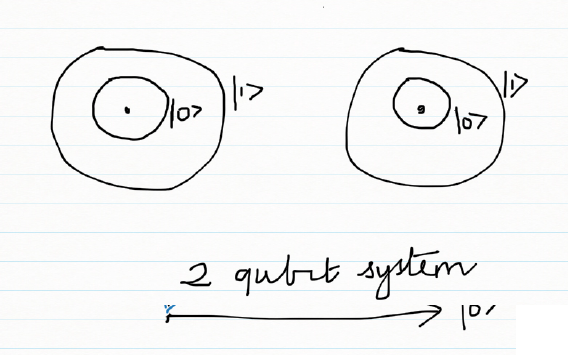

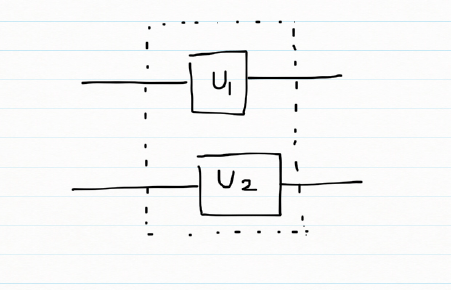

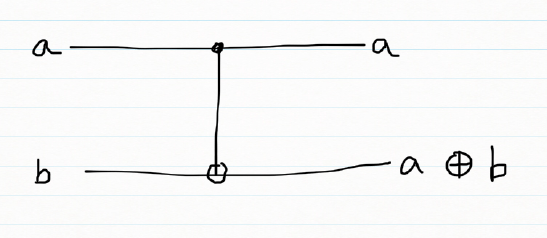

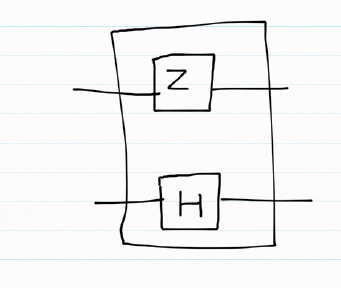

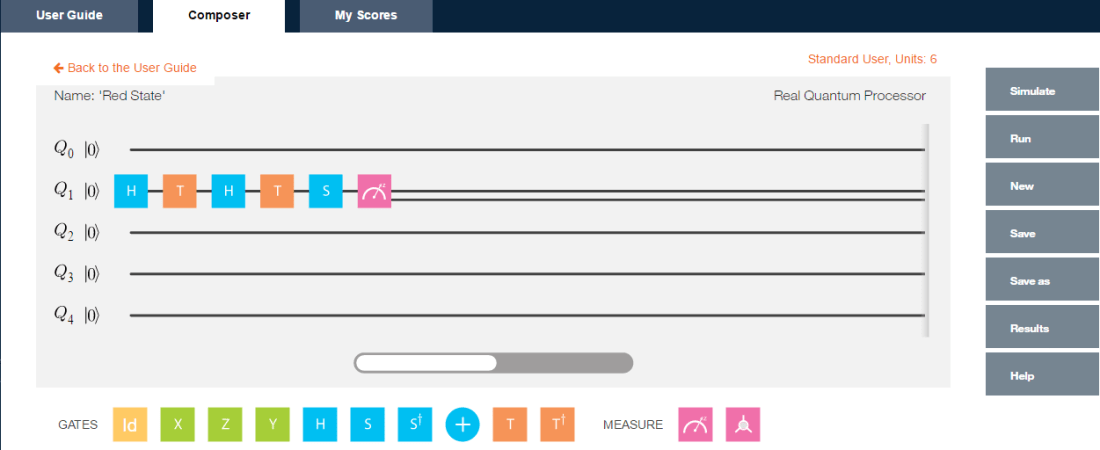

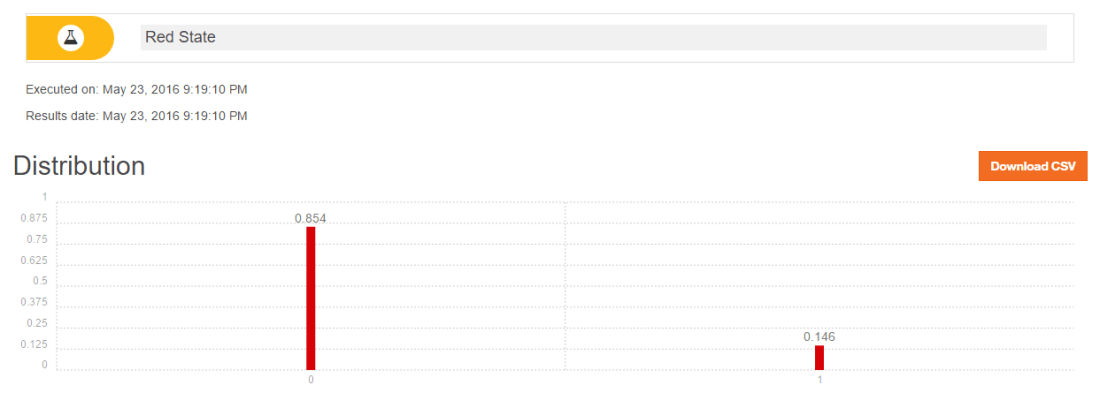

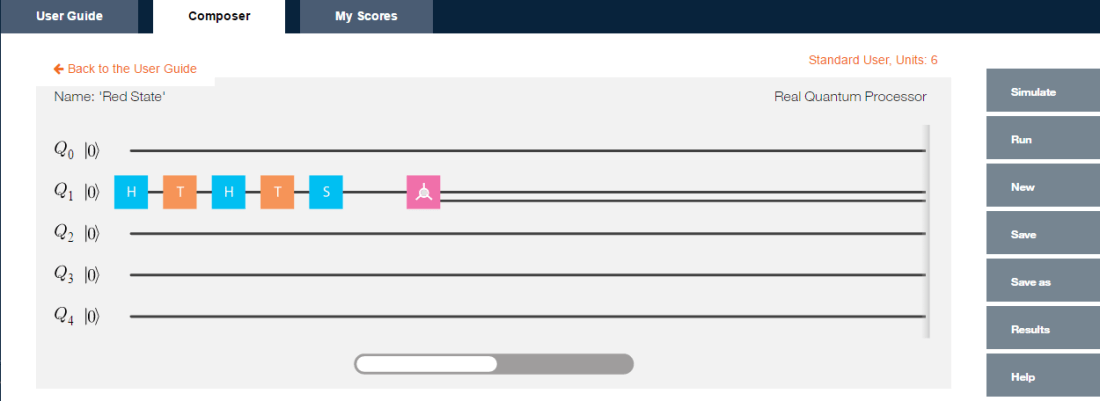

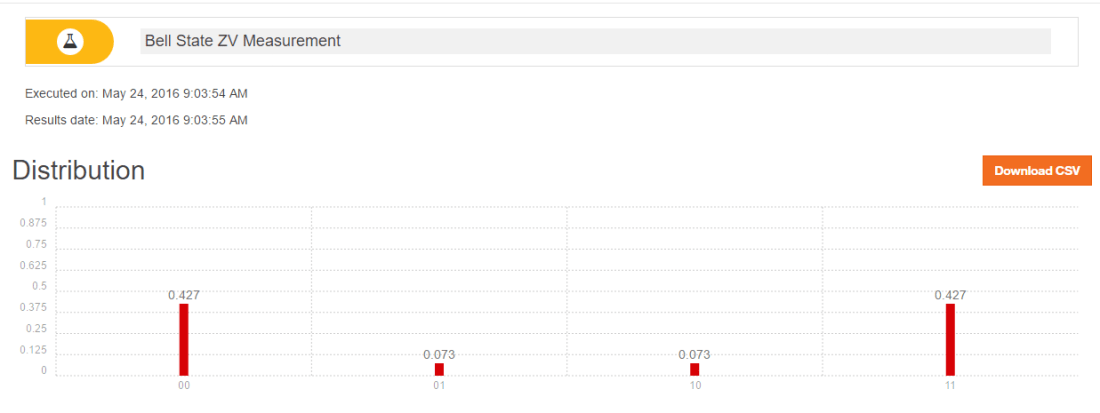

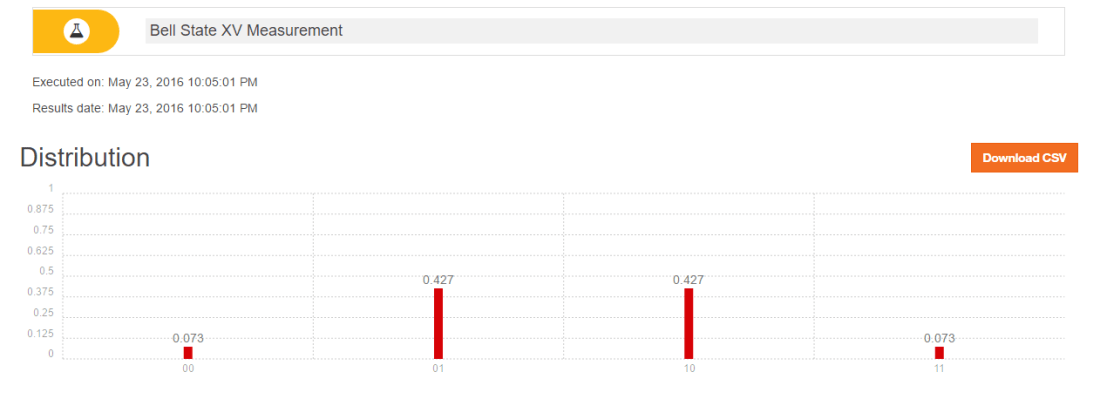

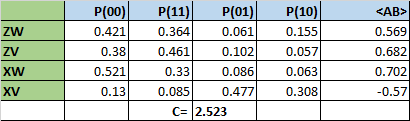

- Introducing QCSimulator: A 5-qubit quantum computing simulator in R

- Deblurring with OpenCV: Weiner filter reloaded

- Rock N’ Roll with Bluemix, Cloudant & NodeExpress

- Introducing cricket package yorkr: Part 1- Beaten by sheer pace!

- Fun simulation of a Chain in Android

- Beaten by sheer pace! Cricket analytics with yorkr in paperback and Kindle versions

- Introducing cricketr! : An R package to analyze performances of cricketers

- Cricket analytics with cricketr!!!

For more posts see Index of posts